Pulmonary valve stenosis is a condition in which a deformity on or near your pulmonary valve narrows the pulmonary valve opening and slows the blood flow. The pulmonary valve is located between the lower right heart chamber (right ventricle) and the pulmonary arteries. Adults occasionally have pulmonary valve stenosis as a complication of another illness, but mostly, pulmonary valve stenosis develops before birth as a congenital heart defect.

Pulmonary valve stenosis ranges from mild to severe. Mild pulmonary stenosis doesn't usually worsen over time, but moderate and severe cases may worsen and require surgery. Fortunately, treatment is generally highly successful, and most people with pulmonary valve stenosis can expect to lead normal lives. Find Out More >>

A patent foramen ovale (PFO) is a hole in the heart that didn't close the way it should have after birth.

During fetal development, a small flap-like opening — the foramen ovale — is present in the wall between the right and left upper chambers of the heart (atria). It normally closes during infancy. When the foramen ovale doesn't close, it's called a patent foramen ovale.

Patent foramen ovale occurs in about 25% of the normal population, but most people with the condition never know they have it. Learning that you have a patent foramen ovale is understandably concerning, but most people never need treatment for this condition.

A patent foramen ovale is often discovered during tests for other problems. In certain conditions, such as unexplained strokes (cryptogenic stroke) in young people, closure might be recommended by your doctor. Find Out More >>

Tetralogy of Fallot is a rare condition caused by a combination of four heart defects that are present at birth (congenital).

These defects, which affect the structure of the heart, cause oxygen-poor blood to flow out of the heart and to the rest of the body. Tetralogy of Fallot is usually diagnosed during infancy or soon after. However, it might not be detected until later in life in some adults, depending on the severity of the defects and symptoms.

With early diagnosis followed by appropriate surgical treatment, most people who have Tetralogy of Fallot live relatively normal lives.

Many adults with repaired Tetralogy of Fallot will require another procedure or intervention during their lifetimes. It is important to have regular follow-up with a cardiologist trained in congenital heart disease who can evaluate you and determine the appropriate timing of another intervention or procedure. At the Irish Congenital Heart Centre, our specialists have trained in congenital heart disease and are expert at caring for people with Tetralogy of Fallot. Find Out More >>

Partial anomalous pulmonary venous return, sometimes called partial anomalous pulmonary venous connection, is a heart defect present at birth (congenital) in which some of the pulmonary veins carrying blood from the lungs to the heart flow into other blood vessels or into the heart's upper right chamber (right atrium), instead of correctly entering the heart's upper left chamber (left atrium). This causes some oxygen-rich blood from the lungs to mix with oxygen-poor blood before entering the right atrium.

Some people with this defect also have a hole between the upper heart chambers (atrial septal defect), which allows blood to flow between the upper heart chambers (atria). People with this condition may also have other congenital heart defects. Find Out More >>

Ebstein anomaly is a rare heart defect that's present at birth (congenital). In Ebstein anomaly, your tricuspid valve — the valve between the two right heart chambers (right atrium and right ventricle) — doesn't work properly. The tricuspid valve sits lower than normal in the right ventricle, and the tricuspid valve's leaflets are abnormally formed. Blood may leak back through the valve, making your heart work less efficiently. Ebstein anomaly may also lead to enlargement of the heart or heart failure.

A significant proportion of people with Ebstein anomaly will also have a communication between the top two chambers of the heart - an atrial septal defect (ASD). Abnormal electrical activity of the heart, leading to abnormal heartbeats (arrhythmia) is also a common problem for people with Ebstein anomaly.

If you have no signs or symptoms associated with Ebstein anomaly, careful monitoring of your heart may be all that's necessary. If signs and symptoms bother you, or if the heart is enlarging or becoming weaker, treatment for Ebstein anomaly may be necessary. Treatment options include medications and surgery. Find Out More >>

An atrial septal defect (ASD) is a hole in the wall between the two upper chambers of your heart (atria). The condition is present at birth (congenital). Small defects may never cause a problem and may be found incidentally. It's also possible that small atrial septal defects may close on their own during infancy or early childhood.

Large and long-standing atrial septal defects can damage your heart and lungs. An adult who has had an undetected atrial septal defect for decades may have a shortened life span from heart failure or high blood pressure that affects the arteries in the lungs (pulmonary hypertension). Surgery may be necessary to repair atrial septal defects to prevent complications. Find Out More >>

Atrioventricular canal defect is a combination of heart problems resulting in a defect in the centre of the heart. The condition occurs when there's a hole between the heart's chambers and problems with the valves that regulate blood flow in the heart.

Sometimes called endocardial cushion defect or atrioventricular septal defect, atrioventricular canal defect is present at birth (congenital). The condition is often associated with Down Syndrome.

Atrioventricular canal defect allows extra blood to flow to the lungs. The extra blood forces the heart to overwork, causing the heart muscle to enlarge.

Untreated, atrioventricular canal defect can cause heart failure and high blood pressure in the lungs. Doctors generally recommend surgery during the first year of life to close the hole in the heart and to reconstruct the valves. Find Out More >>

Bicuspid aortic valve is the commonest form of congenital heart disease. Approximately 1% of the population are born with this condition.

A bicuspid aortic valve is an aortic valve that has only two leafelts (bicuspid) instead of the normal three leaflets (tricuspid) . Some people may also be born with one (unicuspid) or four (quadricuspid) leaflets, but these are rare.

A bicuspid aortic valve may cause the heart's aortic valve to narrow (aortic valve stenosis). This narrowing prevents the valve from opening fully, which reduces or blocks blood flow from the heart to the body. In some cases, the bicuspid aortic valve doesn't close efficiently, causing blood to leak backward into the left ventricle (aortic valve regurgitation). Some people with a bicuspid aortic valve may develop an enlarged aorta — the main blood vessel leading from the heart (see also our Aortopathy section)

Most people with a bicuspid aortic valve aren't affected by valve problems until they are adults, and some may not be affected until they are older adults. However if you are known to have a biscupid aortic valve, you should be followed up by a cardiologist at regular intervals. Find Out More >>

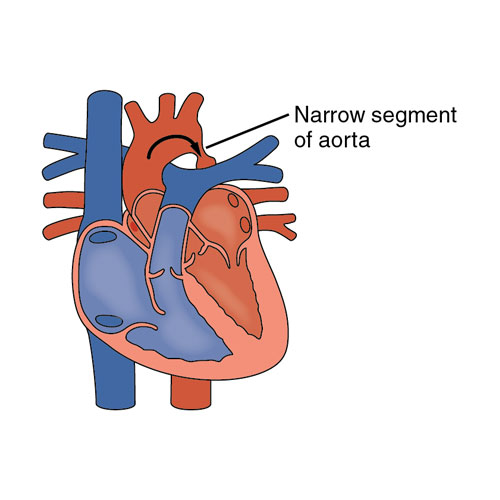

Coarctation of the aorta — or aortic coarctation — is a narrowing of the aorta, the large blood vessel that branches off your heart and delivers oxygen-rich blood to your body. When this occurs, your heart must pump harder to force blood through the narrowed part of your aorta.

Coarctation of the aorta is generally present at birth (congenital). The condition can range from mild to severe, and might not be detected until adulthood, depending on how narrowed the aorta is.

Coarctation of the aorta often occurs along with other heart defects. While treatment is usually successful, the condition requires careful lifelong follow-up. Find Out More >>

A ventricular septal defect (VSD) is a type of hole in the heart. It is present at birth (congenital). The hole (defect) occurs in the wall (septum) that separates the heart's lower chambers (ventricles) and allows blood to pass from the left to the right side of the heart. This means that oxygen-rich blood then gets pumped back to the lungs instead of out to the body, causing the heart to work harder.

A small ventricular septal defect may cause no problems, and many small VSDs close on their own. Medium or larger VSDs may need surgical repair early in life to prevent complications. Find Out More >>

Transposition of the great arteries is a serious but rare heart defect present at birth (congenital), in which the two main arteries leaving the heart are reversed (transposed). The condition is also called dextro-transposition of the great arteries. A rarer type of this condition is called levo-transposition of the great arteries.

Transposition of the great arteries changes the way blood circulates through the body, leaving a shortage of oxygen in blood flowing from the heart to the rest of the body. Without an adequate supply of oxygen-rich blood, the body can't function properly and your child faces serious complications or death without treatment.

Transposition of the great arteries is usually detected either prenatally or within the first hours to weeks of life.

Corrective surgery soon after birth is the usual treatment for transposition of the great arteries, and with proper treatment, the outlook is promising.

Even when this condition is diagnosed and treated early in childhood, there is a potential to develop complications later in life. All people with Transposition of the Great Arteries should have lifelong follow up with a congenital heart specialist. Our experts at the Irish Congenital Heart Centre are trained in congenital cardiology and have vast experience in treating people with Transposition of the Great Arteries. Find Out More >>

Hypoplastic left heart syndrome is a complex and rare heart defect present at birth (congenital). The left side of the heart is critically underdeveloped in hypoplastic left heart syndrome.

If your baby is born with hypoplastic left heart syndrome, the left side of the heart can't effectively pump blood to the body. Instead, the right side of the heart must pump blood to the lungs and to the rest of the body.

Medication to prevent closure of the connection (ductus arteriosus) between the right and left sides, followed by either surgery or a heart transplant, is necessary to treat hypoplastic left heart syndrome.

With advances in care, the outlook for babies born with hypoplastic left heart syndrome is better now than in the past. All people who are born with hypoplastic left heart syndrome will have undergone multiple complex cardiac surgeries and require lifelong follow up by a specialist congenital heart expert. Find Out More >>